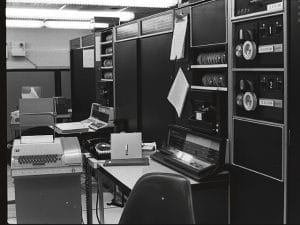

An electrical engineer, Tomlinson worked for Bolt, Beranek and Newman, which had been hired by the U.S. Government to develop the ARPAnet — the Advanced Research Projects Agency packet-switched computer network, which was the forerunner of the Internet. Tomlinson worked in a lab that had two PDP-10 minicomputers; they were right next to each other, but linked only by the early ARPAnet. At the time, there was such a thing as email, but it only worked on the same computer: a message could be sent from one user on the computer to another. But ARPAnet, first created in 1969, was about networking, and in late 1971 Tomlinson came up with an innovation that would allow email to be sent from a user at one computer to someone at another computer: networked email. He came up with an addressing standard to do it: the user login name “at” the computer’s name; he used the @ symbol for that, since it both made sense, and wasn’t used by other programs. That basic standard is still used today. The first email was sent from Tomlinson, sitting at the Model 33 teletype on one of the PDP-10s, to his account on the other PDP-10. Thus the first inter-machine email was sent to himself from himself, between two computers right next to each other, and he just rolled his chair from one teletype to the other to see whether it worked. The message had no real content: probably just some random characters, Tomlinson said later. “The first email is completely forgettable,” he said, “and, therefore, forgotten.” He didn’t even record the exact date.

But once he was satisfied it all worked, the first “real” message was sent to the rest of the ARPAnet team: it announced the new network mail function, and details on how to use it. Tomlinson had gone on to create the software services necessary for moving mail between machines (“mail transport”), the protocols to do so (such as the format for the To, From, Subject, and Date fields), the software needed to drop the message into the recipient’s inbox, and the software needed to read and reply to messages. Tomlinson realized that network email would have an enormous impact. “What I didn’t imagine was how quickly that would happen.” By 1973, email constituted 75 percent of ARPAnet traffic. It wasn’t until about 1994 that the Internet got into popular consciousness in the U.S., but by 1996, more email was sent in the U.S. than postal mail. (Sadly, in 2003, spam became the majority of email, and by 2010, was more than 89 percent of 107 trillion emails sent.) Tomlinson’s work “brought about a complete revolution, fundamentally changing the way people communicate,” says the Internet Society’s Internet Hall of Fame, which inducted Tomlinson in 2012. “Email remains the most popular [Internet] application,” with users “spanning the globe and communicating across the traditional barriers of time and space.” Yet when Tomlinson showed a BBN colleague what he did with that first inter-machine email, he told his co-worker, “Don’t tell anyone! This isn’t what we’re supposed to be working on.” Tomlinson died March 5 from an apparent heart attack. He was 74.

Also See: BBN Founder Leo Beranek